What is Prevention?

Prevention is a process that works to prevent or limit the development of problems associated with mental health challenges or substance use such as alcohol, nicotine, marijuana or other drugs.

Prevention approaches focus on helping people develop the knowledge, attitudes and skills they need to make good choices or change harmful behaviors. Mental and Substance Use Disorders make daily activities difficult and impair one's ability to work, function and manage interpersonal relationships. They are one of the leading causes of disability in the U.S. and can also cause other chronic diseases, like diabetes and heart disease.

As adults, we have a responsibility to do everything we can to make sure our young people grow up to have healthy, strong futures. One thing that stands in the way of that is drug and alcohol use. Drinking and substance misuse can negatively affect young people’s school performance, future job prospects, and physical and mental health, damaging their lives well into adulthood. But together, this is something we can prevent from happening. It’s our job to support policies and programs that prevent and reduce drug use among adolescents.

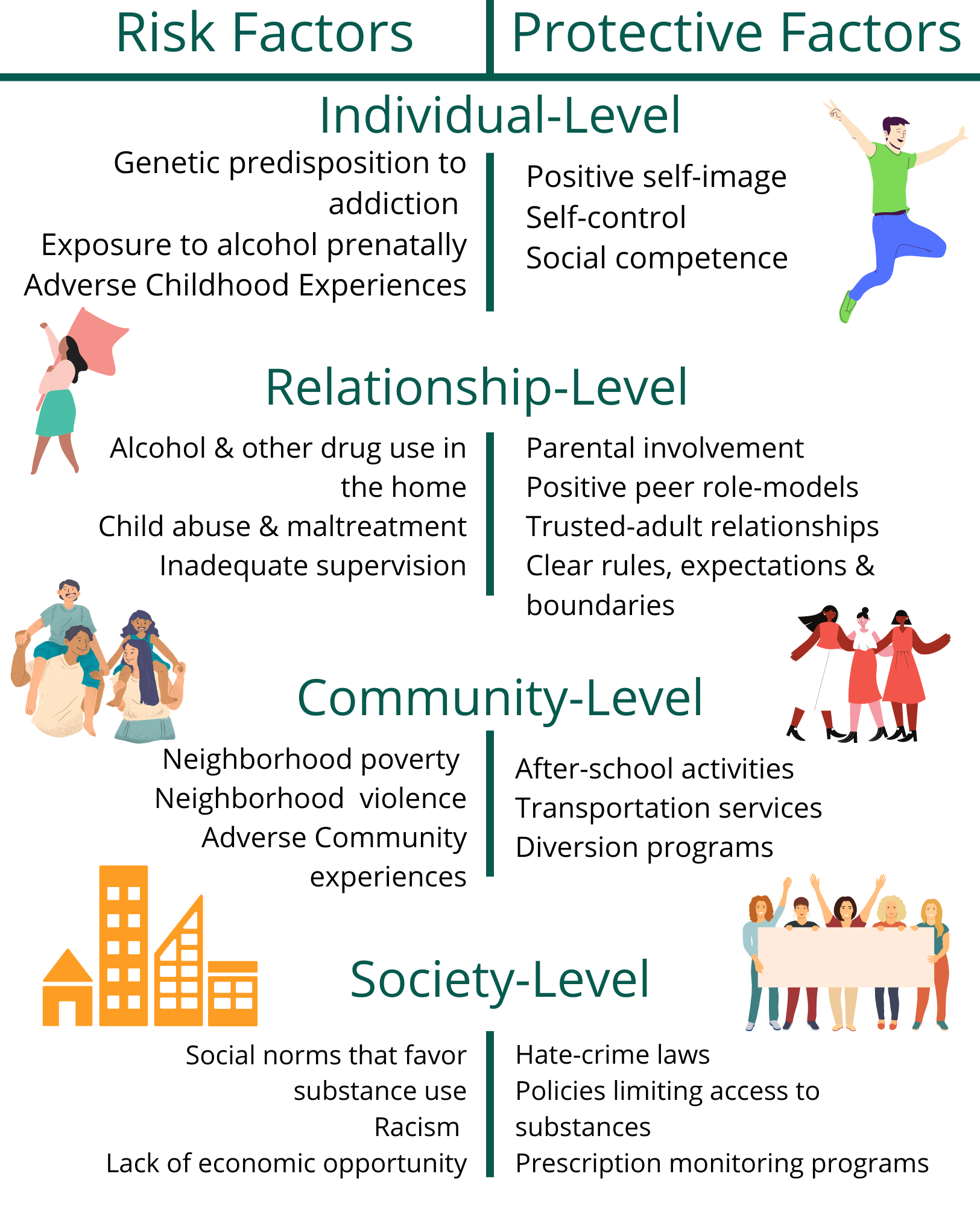

The human brain is not fully developed until the age of 25.

The parts of the brain that develop first are those that control physical activity, emotion, and motivation. The prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for impulse control, reasoning and good judgment, develops last.

Outside influences, like drugs and alcohol are more likely to cause damage to developing brains. This means substance use during the teen years creates a greater risk for immediate and lasting harm.

Healthy adults are usually able to control impulses when necessary because of the judgment and decision-making circuits located in their prefrontal cortex. However, with substance use disorders, these prefrontal circuits are disrupted, resulting in reduced ability to control powerful impulses toward alcohol or drug use.

Many substances, like drugs and alcohol, can alter a person’s thinking and judgment, and can lead to health risks, including addiction, impaired driving, infectious disease, and adverse effects on pregnancy.

More information about the impact of commonly used drugs on the brain and body can be found here:

- Cannabis

- Cigarettes and other Tobacco Products

- Cocaine

- Fentanyl

- Hallucinogens

- Heroin

- Inhalants

- MDMA (Ecstasy/Molly)

- Methamphetamine

- Over the Counter (OTC) Medicine

- Prescription Central Nervous System Depressants

- Prescription Opioids:

- Prescription Stimulants

- Synthetic Cannabinoids (K2/Spice)

- Synthetic Cathinones (Bath Salts)

- Kratom

- Alcohol Health Effects on the body

Sources:

1. https://drugfree.org/article/teen-brain-development/

2. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/commonly-used-drugs-charts

3. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/drugsbrain

4. https://nida.nih.gov/drug-topics/publications/drug-facts

Signs of Substance Use Disorder

Behavioral Changes

- Drop in attendance and performance at work or school

- Frequently getting into trouble (fights, accidents, illegal activities)

- Using substances in physically hazardous situations such as while driving or

operating a machine - Engaging in secretive or suspicious behaviors

- Changes in appetite or sleep patterns

- Unexplained change in personality or attitude

- Sudden mood swings, irritability, or angry outbursts

- Periods of unusual hyperactivity, agitation, or giddiness

- Lacking motivation

- Appearing fearful, anxious, or paranoid, with no reason

Social changes

- Sudden change in friends, favorite hangouts, and hobbies

- Legal problems related to substance use

- Unexplained need for money or financial problems

- Using substances even though it causes problems in relationships

Physical Changes

- Bloodshot eyes and abnormally sized pupils

- Sudden weight loss or weight gain

- Deterioration of physical appearance

- Unusual smells on breath, body, or clothing

- Tremors, slurred speech, or impaired coordination

Signs of Mental Health Challenge

Trying to tell the difference between what expected behaviors are and what might be the signs of a mental illness isn't always easy. There's no easy test that can let someone know if there is mental illness or if actions and thoughts might be typical behaviors of a person or the result of a physical illness. Each illness has its own symptoms, but common signs of mental illness in adults and adolescents can include the following:

Signs of Mental Health Challenge

- Excessive worrying or fear

- Feeling excessively sad or low

- Confused thinking or problems concentrating and learning

- Extreme mood changes, including uncontrollable “highs” or feelings of euphoria

- Prolonged or strong feelings of irritability or anger

- Avoiding friends and social activities

- Difficulties understanding or relating to other people

- Changes in sleeping habits or feeling tired and low energy

- Changes in eating habits such as increased hunger or lack of appetite

- Changes in sex drive

- Difficulty perceiving reality (delusions or hallucinations, in which a person

experiences and senses things that don't exist in objective reality) - Inability to perceive changes in one’s own feelings, behavior or personality (”lack of

insight” or anosognosia) - Overuse of substances like alcohol or drugs

- Multiple physical ailments without obvious causes (such as headaches, stomachaches, vague and ongoing “aches and pains”)

- Thinking about suicide

- Inability to carry out daily activities or handle daily problems and stress

- An intense fear of weight gain or concern with appearance

Mental health conditions can also begin to develop in young children. Because they are still learning how to identify and talk about thoughts and emotions, their most obvious symptoms are behavioral.

Signs of Mental Health Challenges in Children

- Changes in school performance

- Excessive worry or anxiety, for instance fighting to avoid bed or school

- Hyperactive behavior

- Frequent nightmares

- Frequent disobedience or aggression

- Frequent temper tantrums

Source:

https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Warning-Signs-and-Symptoms

Signs of Suicidality:

There are common signs that a person is thinking about suicide.

Thinking About

- Wanting to die

- Great guilt or shame

- Being a burden to others

Feeling

- Extremely sad, anxious, agitated, or angry

- Unbearable emotional or physical pain

- Empty, hopeless, trapped, or having no reason to live

Changing Behavior

- Making a plan or researching ways to die

- Withdrawing from friends

- Saying goodbye, giving away important items, or making a will

- Taking dangerous risks

- Displaying extreme mood swings

- Eating or sleeping more or less

- Using drugs or alcohol more often

Source:

https://www.nami.org/About-Mental-Illness/Warning-Signs-and-Symptoms

How to Have the Conversation - Substance Use

If you notice a friend or loved one experiencing a substance use challenge, you may want to help, but might not know what to say or what to do. One of the first and most important steps you can take is to start the conversation and create a safe space where your loved ones feels comfortable talking about their experience.

To express support, you must be an effective and compassionate communicator. When you know what to say and what to do, you can be the difference in the life of a loved one who may be experiencing an addiction challenge, and ultimately help them move toward recovery by pointing them to appropriate professional, peer or self-help strategies.

10 tips for talking about substance use:

- Talk with them in a quiet place when both of you are sober and calm.

- Let the person know you are concerned and willing to help.

- Consider the person’s readiness to talk about their substance use.

- Identify and discuss their behavior rather than criticize their character.

- Express your point of view by using “I” statements like, “I have noticed…” or, “I

am concerned…” - Listen without judging the person an immoral or “bad.”

- Treat the person with dignity and respect.

- Do not force the person to admit they have a problem.

- Do not label or accuse the person of being an “addict.”

- Have realistic expectations of the person. Their behavior will not change right away.

Talking about addiction can be difficult, and your words of support may not be well

received initially. But don’t get discouraged. Recovery from addiction is possible and

your willingness to start a conversation may ultimately help someone get on the path to

recovery.

How to Have the Conversation - Mental Health

Talking about mental health can be difficult and awkward, but it doesn’t have to be. Nor do you need to be an expert to engage in conversations about mental health. Just a few small words – like asking someone how they’re feeling – can make a huge difference. Whether someone is ready to have that conversation with you or not, most people will appreciate your care and support in trying to start the conversation in the first place.

If you’re not exactly sure where to begin, here are a few helpful conversation starters to break the ice around a loved ones’ mental health:

1.“Are you okay?” Ask the question and mean it. Show you are listening by sitting

alongside the person, maintaining an open body position and maintaining

comfortable eye contact.

2.“Are you thinking about suicide?” If you are concerned that someone is

considering suicide, ask the question directly. Asking a person if they have been

thinking about suicide or have made plans will not increase the risk that they will

complete suicide.

3.“I’ve noticed that…” Open the conversation by explaining behavior changes you

have noticed. For example, “I’ve noticed that you’ve been showing up to work late

a lot lately.” Then, express genuine concern.

4.“Do you want to take a walk?” Engaging a friend, family member or loved one you

are concerned about in a health activity like taking a walk together can be a great

way to start a conversation. Doing an activity while you talk can take some of the

nerves and discomfort out of the conversation.

5.“How are you, really?” Sometimes when someone says they’re fine, they’re not.

Know the warning signs to look for so you can know when to offer extra support.

No matter the path this conversation takes, be prepared to walk it with whomever you’re reaching out to. We want everyone to feel confident to begin a conversation about mental health, sustain that conversation and direct people to the help they may need – whether that’s professional help or just a non-judgmental listening ear.

Source:

How to Have the Conversation - Suicide

Lean in: The only real way to know is to ask. If you observe behaviors or signs that worry

you, ask. The worst thing that will happen if you’re incorrect is that you may feel a bit

embarrassed. Suicidal thoughts are often significant red flags that something is wrong;

varying degrees of intensity are common for people going through hard times. When

you feel your “Spidey senses” tingle or you wonder, “Should I be worried?”—lean in. Ask.

Know your resources: Be familiar with the support resources you have in your community. Some examples might be a school counseling center, an employee assistance program, a local community mental health agency, or national crisis support resources like the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or the Crisis Text Line. Walk into this conversation as a well-informed referral source.

Get comfortable feeling uncomfortable: For most people, asking about suicide is anxiety provoking—and that makes sense. Talking about life and death is intense. Notice and acknowledge your feelings, and do your best to get centered before you start the conversation. Your physical and emotional presence will have a big impact on how the conversation goes. So, take some deep breaths and focus your heart on compassion.

Create a Safe Space: Find a place for privacy and comfort. Depending on the situation, this may mean taking a walk outside or finding a quiet place to sit down. Take cues from the person about physical proximity and intensity of eye contact. Some people prefer to talk shoulder-to-shoulder, others face-to- face. If you’re sitting, make sure that your body language communicates openness and interest and that you’re seated on a parallel level with the person you’re talking to. Take time to turn off your phone and close the door as well, so you won’t be interrupted.

Start with "I've noticed...": Thank them for taking time to speak with you, and list the observations you’ve made that led you to be concerned. Speak about specific times and places where they were not themselves. Maybe you’ve noticed a change in mood, like they’re much more irritable than usual. Maybe you’ve noticed a change in behavior, like they’re drinking more. Maybe you’ve learned that they recently separated from their

spouse or partner.

Ask Open-Ended Questions: To get the conversation going, ask open-ended questions like, “I’d like to understand more about what you’re going through. Can you tell me more?”

Practice Active Listening: Refrain from problem-solving and advice-giving. Instead, show them that they are being heard. Use minimal encouragers like nodding your head, and saying, “uh huh” and “and then what happened” to keep the conversation going.

Tips on asking the suicide question:

- Frame the question with empathy and compassion

“You know, sometimes when people are going through what you’re going through, they find themselves in unimaginable pain. Thoughts like, ‘I wish I could go to bed and not wake up in the morning’ enter their mind because their pain has exceeded their ability to cope.”

- Assume that suicide is "on the menu"

Because suicidal thoughts are common for people who feel overwhelmed, you can say something like, “Sometimes when emotional pain is so intense, people think about suicide. I’m wondering how many times suicide might have crossed your mind, even if just fleeting in nature.” - Use direct language

Using the word “suicide” in a direct way says, “We can talk about this here.” It’s important to use the direct language of “suicide” rather than “hurting yourself,” because these are different questions.

Tips on what to do after asking the question:

If the answer is "No": Notice any nonverbal cues. If they’re defensive and can’t keep eye contact, chances are something else is going on behind these behaviors. In these cases, try pointing out the discrepancy and say, “You’re telling me you’re fi ne, but you seem unable to make eye contact with me. Can you help me understand this?” In these cases, you may need to persist by asking the question in different ways. If the “no” really is a “no,” people will likely express gratitude that you cared enough to reach out and will continue to talk about their troubles.

If the response is not clear: Sometimes people will respond with a question like, “What do you think?” or they’ll say something like, “No, not really.” Sometimes they won’t answer the question at all and will just launch into another story. In these situations, the answer is usually “yes.” Again, point this out: “When I asked you a direct question about suicide, you said XYZ, so am I correct to assume suicide is on your mind? I can appreciate the many reasons you might be hesitant to share this with me, but I’m hoping we can be as open as possible right now, so I can help you.”

If the answer is "Yes": The first words out of your mouth should be, “Thank you.” Express gratitude for the trust they have in you and for how they value your relationship. The second thing you should say is a sentiment of partnership—something like, “I’m on your team, and we’ll figure this out together. I do not want you to die.” The third thing to say is an offering of hope: “I have some things we can check out. If we helped you feel less miserable, my guess is you would no longer consider suicide. So let’s work on that together.”

Build in choice and take action in the moment: Many people who experience suicidal thoughts feel like they have lost control of their own lives. Suicide feels like something they could have control over. To help them reclaim a sense of self-agency, it’s important to build in choice points. For example, ask if they want to call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or the Crisis Text Line. Ask if they want to lead the conversation with the counselor on the other end, or if they want you to. However, if they disclosed a plan of how they might die by suicide, it is imperative to have a mental health professional decide what the next steps should be. Say, “Suicide is too big of an issue for me to handle alone. I need help helping you. I’d like to refer you to a medical professional, who is trained and has access to additional resources.”

Follow up: Sometimes it’s a plan for coffee or lunch. Sometimes it’s a walk in a nearby park or a trip to the beach. Sometimes it’s a simple phone call or an extra stop to their place on your way home from work. No matter what it looks like, make a specific plan for follow-up by saying something like, “I’m going to reach out tomorrow to see how you’re doing.” Following up can make a world of difference, regardless of how the conversation went.

Source:

https://www.nami.org/Blogs/NAMI-Blog/September-2019/How-to-Ask-Someone-About-Suicide

Co-occurring Disorders

Dual Diagnosis or Co-Occurring Disorders are when someone has been diagnosed with a substance use disorder as well as a mental health disorder. Some providers are only qualified to treat someone’s mental health or substance use disorder alone, but it is important to treat both disorders at the same time for the best possible outcome. Mental health and substance use disorders affect people from all walks of life and all age groups. These illnesses are common, recurrent, and often serious, but they are treatable and many people do recover.

Safe Storage and Disposal of Substances (Reducing Access)

Safe Storage and Disposal of Substances (Reducing Access)

A majority of substances are obtained from family and friends, often from the home or medicine cabinet. Safely and securely store substances, like alcohol, tobacco, vaping products, and other substances up and away from youth and visitors. Keep track of substances within your home, including alcoholic beverages and/or other substances that may be stored within a refrigerator.

Make sure others can't access the medications in your home by following these steps:

- Monitor household medications by tracking refills and taking note of how many

pills are in each of your prescription bottles or pill packets. - Secure household medications, both prescription and over-the-counter, by

keeping them out of sight and out of reach. If possible, store them in a locked

container that others cannot access. - Dispose of expired or unused medicine. The ideal way to do this is through

drug disposal programs like the DEA’s Takeback Day. However, there are safe

practices for at home disposal, like drug deactivation bags - Talk to your family and seek help if you or a loved one is misusing or abusing

prescription medications

How to reduce access to lethal means in your home:

https://zerosuicide.edc.org/resources/resource-database/counseling-access-lethal-means-calm

Social Norms and Behaviors

Social Norms and Behaviors

Social norms are unwritten rules of behavior shared by members of a given group or society. Examples from western culture include: forming a line at store counters, saying 'bless you' when someone sneezes, or holding the door for the person after you.

Since drug-related attitudes and behaviors are often acquired through peer group interactions, expectations of how one’s peer group might react have a strong impact on whether young people choose to use drugs. Youth perceptions of their parents’ opinions about substance use are another important factor. In families where parents use illegal drugs, are heavy users of alcohol, or are tolerant of use by their children, children are more likely to experience substance misuse in adolescence.

A person's perception of the risks associated with substance use can be important as to whether or not they engage in substance use. Kids’ attitudes around substance use are influenced very early on by media portrayals of substance use. Positive associations formed at a young age may be predisposing to early substance use. Being aware of outside influences is an important first step to countering its ill effects. Media portrayals of substances such as cigarettes and alcohol are likely leading to positive associations between substance use and social standing/inclusion/desirability.

A person's perception of the risks associated with substance use can be important as to whether or not they engage in substance use. Kids’ attitudes around substance use are influenced very early on by media portrayals of substance use. Positive associations formed at a young age may be predisposing to early substance use. Being aware of outside influences is an important first step to countering its ill effects. Media portrayals of substances such as cigarettes and alcohol are likely leading to positive associations between substance use and social standing/inclusion/desirability.

Countering this influence needs to start early as many of these positive associations are created as early as elementary school and precede and possibly promote youth substance use.

Source:

2021 YRBS Syndemic Analysis by Growth Partners

What is stigma: Stigma is a negative attitude or belief towards a person, place, or culture that is based on a characteristic. Stigma is often based on assumptions and generalizations rather than facts, and can often involve the use of derogatory language and cause further discrimination. One easy way to help reduce stigma is to use safe, person-first language when talking about substance use disorder or mental health conditions.

What is stigma: Stigma is a negative attitude or belief towards a person, place, or culture that is based on a characteristic. Stigma is often based on assumptions and generalizations rather than facts, and can often involve the use of derogatory language and cause further discrimination. One easy way to help reduce stigma is to use safe, person-first language when talking about substance use disorder or mental health conditions.

Why Safe Language is important: Using safe, person-first language allows you to describe a person’s condition, without labeling or defining them by it. It also helps us avoid stigma, punitive attitudes, and shame towards a person who has/had substance use disorder or a mental health condition. Reducing stigma can help people recover and can help them continue to lead healthy lives.

Negative attitudes towards people based on certain distinguishing characteristics. Stigma contributes significantly to negative health outcomes and can pose a barrier to seeking treatment.

Try Saying:

- Person experiencing substance use disorder

- Substance use/Substance misuse

- Person in recovery/ long-term recovery

- Recurrence

- Abstinent from drug use

- Maintained recovery

- Person with alcohol use disorder

- Substance use disorder

- Person with a mental health condition

- Person living with (or experiencing)…

Instead of Saying:

- Addict/Junkie/User

- Drug abuse

- Former/Reformed addict

- Relapse

- Clean

- Stayed Clean

- Addiction

- Alcoholic/Drunk

- Habit

- Mentally Ill

- Suffering from …

Other Resources:

- Educate yourself and youth about the dangers of substance use and risky behaviors

- Create and maintain clear and consistent rules and boundaries

- Offer open lines of communication

- Help others identify and understand mixed messages about substance use

- Ensure that youth living in and visiting your home do not have access to substances

- Be a ‘trusted adult’

- Stay active and engaged with your child and youth in your community

- Model healthy behaviors

- Encourage youth participation in substance free events and activities

- Join a local coalition or working group

- Follow local coalitions, organizations and partners that promote prevention, positive youth development and healthy communities

- Advocate for comprehensive alcohol & drug policies in your schools and community

- Create and enforce local laws and policies that promote alcohol, drug and tobacco free public areas and workplaces

- Host, promote, and involve youth in substance-free events in your community

- Celebrate and promote positive substance-free activities, successes and events

- Promoting protective factors*

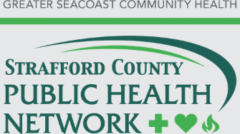

It’s important to know what risk factors are so that you may work towards building protective factors which can help individuals handle adversity better. Protective factors are important because they mitigate the impact of risk factors. They can be both nature and nurture; individual and environmental attributes. It’s important for community members to know what risk and protective factors are so that they can recognize them in themselves and others in order to build a protective network for themselves and their communities.

It’s important to know what risk factors are so that you may work towards building protective factors which can help individuals handle adversity better. Protective factors are important because they mitigate the impact of risk factors. They can be both nature and nurture; individual and environmental attributes. It’s important for community members to know what risk and protective factors are so that they can recognize them in themselves and others in order to build a protective network for themselves and their communities.

It is important for everyone in the community to understand what risk factors are and be able to identify their own risk factors to increase self-awareness and build a protective network for themselves. With this, an individual is better able to then identify and implement protective factors to mitigate the impact of these risk factors.

Risk Factor: A characteristic at the biological, psychological, family, community, or cultural level that precedes and is associated with a higher likelihood of problem outcomes.

Protective Factor: A characteristic associated with a lower likelihood of problem outcomes or that reduces the negative impact of a risk factor on problem outcomes.

ACEs are “potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years)” (CDC, n.d.). Examples of these events include, but are not limited to; experiencing violence, witnessing violence, and/or having a family member attempt or die by suicide. Childhood environments, such as growing up in a household with substance use or behavioral health problems, can also adversely impact early to late childhood development and health complications that may continue into adulthood.

ACEs are “potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years)” (CDC, n.d.). Examples of these events include, but are not limited to; experiencing violence, witnessing violence, and/or having a family member attempt or die by suicide. Childhood environments, such as growing up in a household with substance use or behavioral health problems, can also adversely impact early to late childhood development and health complications that may continue into adulthood.

Using a trauma-informed approach realizes trauma’s impact on an individual or community, recognizes signs and symptoms of trauma, and responds by integrating knowledge of trauma into policies, procedures, and practices while actively resisting re-traumatization in individuals.

Advocacy is educating and creating awareness among legislators and the general public of issues facing the community and the importance of aligning public policy to address the need.

Advocacy is educating and creating awareness among legislators and the general public of issues facing the community and the importance of aligning public policy to address the need.

What you can do:

• Share your story/Submit Testimony

• Educate others in your Community

• Raise Awareness

• Contact your legislator

• Submit a letter to the Editor

• Watch for House bills and open hearings

• Stay informed on local and state policy changes

To Learn more about how to Advocate:

Resources in the Community

Information Dissemination: The sharing of information, tools and resources to increase knowledge and awareness of substance misuse prevention practices, as well as the problems and causes associated with substance use disorder.

Education: The process of building skills and knowledge to help prevent substance misuse, such as decision making, peer resistance, stress management, mindfulness, and interpersonal communication.

Alternative Activities: The process of organizing and participating in healthy and constructive activities that exclude the use of substances.

Problem Identification: The process of identifying, assessing and referring individuals at risk of, or actively misusing substances to services and programs.

Community-Based Process: Prevention efforts that focus on the health outcomes of an entire population, rather than an individual’s.

Environmental: A set of strategies that aim to change standards, codes, and attitudes towards substance misuse within a community. Examples include laws and policies that revolve around substances, like tobacco, marijuana and alcohol, etc.

Risk and Protective Factors: Characteristics that contribute to the development of a substance use disorder. These characteristics exist in individuals, relationships, communities & society. Risk factors can make problem outcomes more likely, while protective factors can help make them less likely.

Social Norms: A prevention practice that focuses on positive messaging about healthy behaviors and attitudes. It is designed to correct misconceptions that normalize substance misuse behaviors.

Ease of Access: An individual’s ability to access substances that they would otherwise not have access to. This strategy focuses on safe practices in sales, prescribing, use, storage and disposal.

Stigma:Stigma is a negative attitude or belief towards a person, place, or culture that is based on a characteristic. Stigma is often based on assumptions and generalizations rather than facts, and can often involve the use of derogatory language and cause further discrimination. One easy way to help reduce stigma is to use safe, person-first language when talking about substance use disorder or mental health conditions.

Perception of Harm: A person’s perception of the risks associated with substance use is an important factor as to whether they engage in substance use itself. For example, people who perceive a higher risk of harm from substance use are less likely to use than those who perceive a lower risk of harm.

Harm Reduction: Strategies and ideas that aim to reduce problem outcomes and harms associated with substance use. This includes safer use, managed use, conditions of use, abstinence and use, itself.

Helpful Links